Shelter Neck’s Unitarian School

The following document was prepared by Eunice Milton Benton in December 1994 as her thesis for her Master’s of Arts Degree in Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. Copyright by Eunice Milton Benton, 1994 All rights reserved.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter I. Southern Work – Unitarianism in the South at the Turn of the Century

Chapter II. The Chronicle of the Carolina Industrial School

- 1900-1910 – The Beginnings of the “Dix House School”

- 1911-1919 – The Heyday of The Carolina Industrial School

- 1920-1926 – The Last Years of the Shelter Neck School

- Managing and Financing of the School

- The Shelter Neck School Properties

Chapter III. Northern Unitarian Women and Southern Backwoods Families

- Personal Sketches

- Chronology of Teachers and Staff (not included)

- Abby A. Peterson Memorial Society document

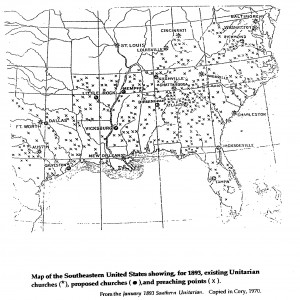

- 1893 Map of Southeastern U. S. from showing Unitarian churches and preaching stations

- Map of Shelter Neck area, showing school site (not included)

- Contemporary Site Plan of Shelter Neck Property, 1993 (not included)

- Photo of Shelter Neck School Students and Teachers (ca. 1915) (not included)

- Photos of Shelter Neck Site, 1993 (not included)

- Program from 1900 Shelter Neck Chapel Dedication (not included)

DEDICATION

This thesis is dedicated toGladys Oliver Milton, my mother, whose lifelong belief in the value of education and whose own example of earning a master’s degree at midlife opened the door for me to follow a similar path, and to

William Grady Benton, my husband, with whom I have shared over a quarter century of living and whose support of women and their work–and of me–is a much appreciated gift. His willingness to underwrite my midlife scholastic work provided the “grant” which allowed this research to be done.

ABSTRACT

At Shelter Neck, North Carolina, a never-incorporated community in the coastal piney woods of Pender County, New England Unitarians established a small church and operated of a school during the first quarter of the twentieth century. Never a strong denomination anywhere in the South, Unitarianism was an unlikely sponsor for a church in the backwater South at the turn of the century. Yet this endeavor erected the first Unitarian church building in North Carolina and offered education to the rural white children of this remote area before the state provided it.

The chronicle of events between 1900 and 1926 which precipitated, sustained, and finally terminated the Unitarian school at Shelter Neck, North Carolina, has never been researched or published. This thesis contains the account of this enterprise, which incorporated as The Carolina Industrial School. This study inquires about the motives of the northern-based philanthropists, the interaction between them and this small Southern community whose economy was based on timber and farming and whose established churches were evangelical, and the influence of their efforts on the community and the school’s students.

Background and Research Method

At Shelter Neck, North Carolina–a never-incorporated community in the coastal piney woods of Pender County–Unitarians based in New England sponsored a small church and operated of a school for most of the first quarter of the twentieth century. The endeavor erected the first Unitarian church in North Carolina and was an attempt to offer education to rural white children in this remote area where the state had not yet provided it.

The story of the educational enterprise which began at Shelter Neck and was later incorporated as The Carolina Industrial School has never been uncovered or reviewed. There were no other Unitarian churches in the state when the chapel, the first building built at the site, was dedicated in November 1900. Never a strong denomination anywhere in the South, that Unitarianism would sponsor a school and church in North Carolina is noteworthy and invites questions about the motives of these northern-based philanthropists, the interaction between them and this small southern community whose economy was based on timber and farming and whose established churches were evangelical, and the impact of their efforts on the community and its members in ensuing years.

The records of the school’s operations indicate that the main sponsor, organizer, and manager of this “Southern Work” was the National Alliance of Unitarian Women. How and why did the organization fix upon this particular community? How was the operation financed and managed? What was the experience of the organizers, ministers and teachers? Of the students? How did the school as an institution interact with the community? What was the long-range impact of the school on its students and on the community at Shelter Neck?

Using a wide variety of resources, this paper will attempt to unearth and examine the story of the Unitarian presence at Shelter Neck. Oral histories from former students of the school and their descendants, minutes of meetings of Unitarian organizations involved with the project, and correspondence between those working in North Carolina and the sponsors in New England will be primary sources. Published works about industrial schools in the South, philanthropies undertaken by women’s groups at the turn of the century, Unitarianism and other pertinent religious groups, and histories and data about Pender County, North Carolina, and the South at the turn of the century will also be consulted.

INTRODUCTION

This is the story of a short-lived North Carolina school which grew from a schoolroom built by a missionary minister. It is a story where Unitarians meet Primitive Baptists and where Yankee women are teachers for Southern backwoods families. It is the story of a few years when a small Southern place coalesced around an institution, founded by outsiders yet accepted by the people of the community as their own. This study documents a quarter century when, in an obscure spot in the South, women of a small religious denomination from a Northern city schooled one generation of rural children. It is a short history of a brief experience in a small place, which, nonetheless, influenced the lives and world views of those who shared it.

The chronicle of events between 1900 and 1926 which precipitated, sustained, and finally terminated the Unitarian school at Shelter Neck, North Carolina, has never been researched or published. The mission of this work is to inform the historical record about these events and to inquire about their significance in the lives of those who experienced them.

Those who are interested in the interaction of religious and cultural groups, those interested in religion in the South, and especially those interested in the Unitarian and Universalist presences in the South will find this account meaningful. But this is not just a story about religion. While the Unitarian movement and its womens’ organization sustained the effort, the story of Shelter Neck is about human and cultural interaction, about people from the urban educated North coming to work with people in an obscure swampy corner of the South. It is a story of the work of women and of a womens’ organization born in the Victorian era–an era when women enjoyed educational privileges never before available but before professional doors fully opened to them, and an era when the concept of settlement work arrived and found an eager audience among educated upper class women. It is the story of an undertaking which rode to a large extent on the shoulders of one dedicated woman, whose death undoubtedly hastened its demise.

Chapter I of this paper provides background for the Shelter Neck story. It focuses primarily on two antecedents of the Shelter Neck school at the turn of the century–the Unitarian presence in the South and the National Alliance of Unitarian Women. Chapter II recounts the history of the school–its founding, curricula and operations, and closing. Chapter III inquires into the motivations, interactions and reactions of the people who shared this experience. It stirs the kettle of cultures, creeds, missions and memorials that mingled at Shelter Neck.

The Executive Board Minutes of the National Alliance of Unitarian and Other Christian Women proved to be the primary source for details about the school’s history. No financial or board meeting records of the Carolina Industrial School have been found. Sources for the story delineated here include the Alliance minutes, articles found in various publications (especially the Christian Register), interviews with former students of the school over a two-year period, and other documents which provided insight into the school’s curricula and activities.

The Shelter Neck school is the main subject of this study, but the Carolina Industrial School, Incorporated, consisted of two schools in North Carolina; the other, at Swansboro, was called the Emmerton School. This paper necessarily touches on the work at Swansboro because, after the Shelter Neck school closed, the work was “consolidated” into the Swansboro facility. Not until all the work of the Carolina Industrial School ended is there closure to this chronicle.

This paper intends to document and is deliberately descriptive. It is ribboned with quoted material because the view of this researcher is that the “voices” of those involved in the story–their own telling of what happened–illuminates events in a way that a recasting of their words could never do. Thus, especially in the second and third chapters, quotes from personal interviews, sections of the Alliance minutes, pieces of Reverend Key’s historical sketch, and passages from articles, correspondence, and documents are liberally used to capture both the chronicle of events and the flavor of the times in which they occurred.

Heard here are the voices of establishment New England Unitarians and their Harvard educated ministers purposing not only to spread the liberal Christian message in the South but also to “induce and establish right thinking and right living.” Recorded here is the chronicle of an effort whose retired leader claimed it had succeeded in “improving the health, elevating the tastes, arousing the ambitions of the people at large, and bearing undeniable testimony to the value of the Carolina Industrial School.”

At Shelter Neck high-minded New Englanders, influenced by the notion of settlement work, led by such examples as the South End Industrial School and the Southern Industrial School, and surely seeing themselves as knights and ladies bringing good clean living to this unkempt community, gave “untiring service” for a quarter of a century.

Obviously the Northern Unitarian backers of the school wished to clean up and pretty up this backwater community. Unarguably their motivation was to extend their own notion of “right living.” Dominant cultures have, throughout history, been prone to extend their cultural ideas to less prominent groups, to attempt to make over lesser ranked societies in their own images. In doing so, such reformers risk exhibiting an inherent disrespect for the cultures of others.

Yet the influence of this effort was limited. Had the Unitarians touched a larger population or stayed longer in Shelter Neck, their influence, whatever its merits, might have been greater. The finest accomplishment of the Unitarian school at Shelter Neck may be that it fostered a sense of community pride, which nurtured individuals in the community and gave them a sense of value and worth. Those who experienced the school as students have fond memories and associations which seem, in their later years, to be sustaining.

Chapter I

SOUTHERN WORK: UNITARIANISM IN THE SOUTH AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURY

Rev. Mr. Chaney said there was no doubt in his mind that the greatest work done for church extension in the next ten or fifteen years will be owing to the work done by the women in the last ten years, and they are bound to do more; to do what the A.U.A. cannot do. National Alliance Minutes – 1891

The late nineteenth-century South, imbued with religious fervor though it may have been, had never embraced Unitarianism. “Overall, liberal churches made little impact on nineteenth century religious life in the Southeast,” concludes Earl Wallace Cory. His 1970 dissertation about nineteenth-century Southern Unitarians and Universalists declares that the efforts of both denominations–they would not merge until 1961–were “only modestly successful” in the region.[1]

Throughout the better part of the century the only Southern Unitarian churches of any size and stability were in the cities of Charleston, New Orleans and Louisville, with a congregation in Richmond intermittently active. Both the Charleston and New Orleans congregations, still the oldest continually functioning Unitarian churches in the South, had been established by 1817. Begun as Presbyterian groups, both these Southern coastal city congregations were sustained through the mid-century years by long-term ministers, the Reverend Samuel Gilman in Charleston and the Reverend Theodore Clapp in New Orleans. In Louisville Bostonian clergyman George Chapman, who had come “at the solicitation of a few earnest and liberal-minded people to whom the principles of Unitarianism had long been dear,” was the minister who helped establish that church in the 1830s.[2] As early as 1833 a congregation had been started in Richmond, but declined into inactivity during the Civil War years and was not revived until the 1890s. Short-lived congregations had also existed in the course of the century in Augusta and Savannah, Georgia, and in Mobile, Alabama.[3]

In addition, a number of unsettled Unitarian ministers, some of whom had been converted from other faiths, roamed the rural South in the latter part of the century. Joseph G. Dukes, in eastern North Carolina, and Jonathan Christopher Gibson, in northwest Florida, were among these. The National Alliance of Unitarian Women would become the primary support for the Reverend Dukes, whose missionary ministry would plant a chapel and school at Shelter Neck, North Carolina.

The Unitarianism that came to the South in the nineteenth century had arisen out of the Reformation and acquired its name for its preference of viewing God as one Being instead of a Trinity. The American denomination had its roots in Massachusetts, where it had been founded in the young American republic by a group of Boston clergy who had moved away from the more orthodox, Calvinist-centered belief system of New England Congregationalists. In its nineteenth-century form, Unitarianism was, primarily, a reaction against Calvinism’s belief that human beings were depraved and threatened with hell. Late nineteenth-century Unitarians considered themselves “liberal Christians,” but Christians nonetheless, and were frequently surprised and offended when more orthodox and conservative religious groups attacked them. “The central idea of Unitarianism was shared by those who bore this name, whether in the North or the South,” points out Cory. “[They] embraced both a denial of the dogma of the Trinity and an emphasis on the unity of God.” Cory also cites another common theme in the faith and its conflict with orthodox Christianity: “Reason increasingly became a hallmark of Unitarianism . . . Those holding the orthodox theology doubted the role of reason, because they considered man’s nature corrupt and dominated by the power of evil.”[4] While in urban Boston Unitarianism was the establishment denomination, the region below Mason Dixon line did not its “reasonable.” Most late nineteenth-century Southerners viewed Unitarianism not only as unorthodox but “Northern” as well.

Young as an American denomination, the Unitarian Church and its liberal religious precepts were confined almost entirely to New England for most of the nineteenth century. By the 1880s and 1890s, however, the Boston-based denomination stepped up efforts to spread the Unitarian message in the South. Its primary goal in the region was to foster churches in the larger cities. Although the last two decades of the century would witness more Unitarian activity in the South than ever before, in the mid-1890s the denomination would reassess its goals and resources and rein in its extension efforts, virtually abandoning some projects and precipitating the resignation of its recently established Southern Superintendent. The National Alliance of Unitarian Women would be called upon to rescue the pioneer work and to nurture those fragile patches in the South where Unitarianism had taken root.

Even though the denomination clearly wanted to promote itself, Unitarians’ outreach activities were less proselytizing than those of more evangelical faiths, and their projects tended to have prominent educational and social aspects. Particularly in the South, the denomination believed that education would lay a foundation for the acceptance of Unitarianism, and that, as Cory asserts, “liberal religion would thrive if the educational level of the southern communities was raised. “[5] In the period immediately after the Civil War, many individual Unitarians supported schools in the South for formerly enslaved African Americans. Later both individual Unitarians and Unitarian organizations aided educational ventures for southern white children.

Historian Cooke explains the Unitarian perspective about reform work:

The belief of Unitarians in the innate goodness of man and in his progress towards a higher moral life, together with their desire to make religion practical in its character and to have it deal with the actual facts of human life, has made it obligatory that they should give the encouragement of their support to whatever promised to further the cause of justice, liberty, and purity. Their attitude towards reforms, however, has been qualified by their love of individual freedom. They have a dread of ecclesiastical restriction and despotism over individual convictions. And yet, with all this insistence upon personal liberty, no body of men and women has ever been more devoted to the furthering of practical reforms than those connected with Unitarian churches.[6]

As early as 1868, in fact, the American Unitarian Association had become involved in reform in the South, focusing especially on the needs of recently enfranchised African Americans. In an agreement that year with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Unitarians furnished $4000, to be used primarily in educational work. In his Unitarianism in America Cooke lists individual Unitarians who “engaged in the work of educating the negroes” during the years immediately following the Civil War: “Rev. Henry F. Edes in Georgia, Rev. James Thurston in North Carolina, Miss M. Louisa Shaw in Florida, Miss Bottume on Ladies’ Island, and Miss Sally Holley and Miss Caroline F. Putnam in Virginia.” During its first eight years the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama received $5000 annually from Unitarians, and leaders at the Hampton Institute in Virginia observed at the turn of the century that “the Unitarian denomination has had a very important part in the work of Hampton.” Mary Hemenway, a Unitarian woman of some means, was the largest single donor to Hampton and also contributed generous sums for other Southern educational work. The Calhoun, Alabama, “Colored School and Settlement,” the first settlement school in the South, which two former Hampton teachers had founded, was supported “mostly by Unitarians.” In early 1886 the American Unitarian Association established a bureau of information about Southern schools; headed by Hampton Institute’s former treasurer, General J. B. F. Marshall, the bureau screened Southern educational ventures worthy of support and contributions for Unitarians interested in them.[7]

In late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century issues of The Christian Register , the major Unitarian periodical of the time, articles about Southern schools abound. Frequently found are letters from the leaders of Tuskegee and Hampton Institutes, as well as stories about the Alabama schools at Calhoun, Snow Hill, and Camp Hill. Northern Unitarians frequently exhibited a preference for backing African American institutions, however, about which a contributor to the The Register , writing after a trip to Camp Hill, complained: “Pure devotion has been invested in this school by its principal and his admirable helpers. Bitterness has often been expressed because northern people will give for Negroes but have no sympathy with the needy white children of the South.”[8] In eastern North Carolina, however, a circuit missionary venture, supported jointly by the American Unitarian Association and the National Alliance of Unitarian Women, would found the Carolina Industrial School, an institution for rural white children.

Unitarians valued education and held reason and rational thinking in high esteem; indeed, observes Cooke, “it has often been assumed that Unitarianism attracts only intellectual persons.”[9] Unitarian Horace Mann had been the first secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education and was later president of Antioch College in Ohio, an institution promoted as “the Harvard of the West” and supported largely by Unitarians. Harvard Divinity School was almost exclusively Unitarian for the first half of the nineteenth century, although in later years it opened up its doors to other denominations under the presidency of Charles W. Eliot.[10] The Proctor Academy, established in Andover, Massachusetts, in 1848, was a Unitarian preparatory school, and the Hackley School, another Unitarian-supported New England preparatory school, was founded in 1900 at the urging of Samuel A. Eliot, son of Charles W. Eliot and then President of the A.U.A. [11]

Closer to the Carolina Industrial School’s site, in Wilmington, North Carolina, a Unitarian woman who had distinguished herself with the Unitarian-supported Sanitary Commission during the Civil War would devote the balance of her life to establishing schools which would become the foundation for the Wilmington public school system. Amy Morris Bradley would be known as “Wilmington’s School Marm.” There is, however, no indication of any interaction between Amy Bradley and the women who taught at Shelter Neck, though the latter small community is only about forty miles north of Wilmington. The two educational efforts by Unitarian women in North Carolina sprang from separate eras and motivations and had no connection. While Amy Bradley’s work received support from the American Unitarian Association, it was substantially finished by the time the A.U.A. and the National Alliance became involved in North Carolina. Bradley died in 1904.[12]

Only as recently as 1825 had the American Unitarian Association been founded, and, “Up to the year 1865 the Unitarians had not been efficiently organized, and they had developed very imperfectly what has been called denominational consciousness, or the capacity for co-operative efforts.”[13] Yet, aided by the circulation of denominational tracts and periodicals, Unitarianism spread westward to the larger cities of Kansas, Illinois, Wisconsin, and California. Given the disturbance of the Civil War and its attendant issues, however, Unitarians directed little or no effort toward the South.

Appomattox ushered in a new era for the country, and for Unitarianism. Writes Cooke:

The war had an inspiring influence upon Unitarians, awakening them to a consciousness of their strength, and drawing them together to work for common purposes as nothing else had ever done. . . Whatever its effect on other religious bodies, the war gave to Unitarians new faith, courage, and enthusiasm. For the first time they became conscious of their opportunity, and united in a determined purpose to meet its demands with fidelity to their convictions and loyalty to the call of humanity.[14]

In the spring of 1865, with victory for the Union assured, Northern Unitarian leaders for the first time called for the raising of a significant sum of money ($100,000) and “a convention . . . to consider the interests of our cause and to institute measures for its good.”[15] Although the resolution of theological issues between conservative Christian and the more “radical” transcendental elements consumed a good deal of the movement’s energy over the next decade, the period between 1865 and 1880 saw a “denominational awakening” and the instigation of an annual National Conference.[16]

In 1885 the establishment by the A.U.A. of “sectional” superintendents, one of which was the Southern Superintendent, set the stage for Unitarian expansion in the South. The influence of the first Southern Superintendent and his wife, the Reverend George L. Chaney and Caroline E. Chaney, profoundly changed the demography of Unitarianism below the Mason Dixon line. By the early 1880s the Reverend Chaney was already doing missionary work in the South and in 1882 was the catalyst for the beginnings of a congregation in Atlanta. Chaney was Southern Superintendent until 1896. During his years in the South the number of Southern cities claiming Unitarian churches increased dramatically. The early 1890s saw the revival of the Richmond congregation as well as the founding of new churches in Chattanooga, Memphis, St. Louis, Austin, San Antonio and Galveston, and the beginnings of more formative groups in Greenville, South Carolina; Jacksonville and Tampa in Florida; Nashville, Tennessee; Asheville and Highlands in North Carolina; and Birmingham, Alabama.

Chaney’s influence not only established new congregations but connected them to each other at meetings of the Southern Unitarian Conference, founded in 1884, and through The Southern Unitarian, a monthly journal published, beginning in 1893, for five years. Although tracts and periodicals printed in Boston also circulated,The Southern Unitarian encouraged the young Southern congregations. The Southern Conference met almost annually for many of those years: in Atlanta in 1887, 1888, and 1894; in Charleston in 1885 and 1892; in Chattanooga in 1889 and 1891; in New Orleans in 1893; and in Memphis in 1897.[17]

While her minister husband was Southern Superintendent, Caroline E. Chaney served on the Board of the National Alliance of Unitarian and Other Christian Women as Vice-President for the Southern States, first elected in the re-organized National Alliance’s first annual meeting in September, 1891. Her voice in the board meetings and her reports at annual conferences were stirring as she championed the causes of fledgling southern churches and isolated missionaries and implored the Alliance’s support for them, once exclaiming that she “wished that words might be given her to express the needs of the South.” [18]

The influence of the Chaneys and Mrs. Chaney’s position with the National Alliance undoubtedly drew the women’s organization into the major role it would play in Unitarian extension in the southeast. The Reverend Chaney, speaking in 1891 at the first annual meeting of the freshly reconstituted National Alliance, urged the women to continue their missionary projects: “Rev. Mr. Chaney said there was no doubt in his mind that the greatest work done for church extension in the next ten or fifteen years will be owing to the work done by the women in the last ten years, and they are bound to do more; to do what the A.U.A. cannot do.”[19]

By the 1890s the National Alliance of Unitarian and Other Christian Women was a busy and dynamic organization, yet, at only ten years old, still a relatively young one. As Jessie E. Donahue has observed, the American Unitarian Association was fifty-three and the National Conference thirteen years old before a Unitarian women’s association organized.[20] While Unitarians had been among the first to support women in education, the ministry, and other professions, no woman appeared as a delegate at the first two National Conferences of the denomination. By the third, in 1868, however, thirty-seven women were delegates, a result undoubtedly inspired by a resolution the previous year suggesting to the member churches the appropriateness of such representation. The denomination had ordained its first woman minister, Celia C. Burleigh, in 1871, only a year after delegates elected Lucretia Crocker the first woman board member for the A.U.A.[21]

The organization of Unitarian church women formally began in 1880 as the Women’s Auxiliary Conference. The first stirrings of Unitarian women, led by Fanny B. Ames, occurred in concert with the meeting of the 1878 National Conference, which appointed a committee of ten women to prepare a plan for an auxiliary organization which would be run by women. “Women had been listeners at all meetings of these organizations [the A.U.A. and the National Conference],” writes Sara Comins in a later history of the Unitarian women’s movement. “Strong personalities had effected reforms in society outside the church, . . suddenly . . . a spark of enthusiastic determination animated these women, led by Mrs. Ames,” she continues.[22]

Growing momentum led to a formal organizational meeting in 1880 at Saratoga, New York, which created the “Women’s Auxiliary Conference.” (The Auxiliary could claim among its founding members some of the activist women of the day–Julia Ward Howe, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Peabody, Dorothea Dix, Kate Gannett Wells, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, and Fanny B. Ames, among others.) The understood intent of the new organization was to involve women in the work of the American Unitarian Association and the National Conference and, thus, the name “auxiliary” was fitting. The Auxiliary’s meetings were planned to coincide with those of the National Conference, to which it made reports and to which it was subsidiary. The male-led American Unitarian Association received and managed all the monies raised by the women’s organization. By 1890, however, enough women were ready for change to support the adoption of a new constitution and a new name: “The National Alliance of Unitarian and Other Liberal Christian Women.” The move caused some alarm:

The change made then in its handling of funds created a near panic. . . Hitherto it had been deemed imprudent and inadvisable for the women’s organization to maintain an independent treasury. For a separate executive body of Unitarian women to disburse its own money was regarded as dangerously revolutionary and the change was accomplished in 1890 only after long and heated debate in the denominational press and among ministers, laymen and the Auxiliary members themselves.[23]

In September 1890 the newly constituted Alliance–its shortened name the one by which it became known–pointed toward the turn of the century with a new structure and new officers, most of whom would shepherd the refocused association through the next decade: Emily A. Fifield was Recording Secretary; Mrs. Robert H. Davis, Corresponding Secretary; Miss Flora L. Close, Treasurer, and, in the chair as President was Mrs. Ward B. Dix. A bevy of Vice-Presidents and Directors represented the various regions and clusters of Alliance branches. Through the last decade of the nineteenth century and into the first several of the twentieth, the Executive Board of the National Alliance would meet monthly, its minutes dutifully recorded in Mrs. Fifield’s neat handwriting, at the headquarters of the American Unitarian Association at 25 Beacon Street in Boston.

The minutes of the Alliance monthly board meetings are a rich source of information and reveal the remarkable level of commitment of its executive officers. The organization’s leaders were as involved in its operations and promotion as the management of any modern corporation. Its officers were almost constantly on the road, and its secretaries generated reams of written records. These women leaders, who clearly believed in the value of face-to-face contact, made frequent excursions into the South, an area which few nineteenth-century Bostonians had visited. In May 1895, for example, “the secretary [probably Mrs. Davis] gave a detailed account of her visit of Baltimore where she had. . . attended all the meetings of the Southern Conference. She had met . . . some of the ministers doing the circuit service’ in which the Alliance is much interested.[24]

To finance its expanding work, the Alliance published, in denominational periodicals and circular letters to its branches, an “appeals list” to request support for its causes. Its Appeals Committee acted as a clearinghouse for the many solicitations and reported regularly to the board.

Of all the Alliance projects in those years, none was more successful than the “Post Office Mission.” Well suited to the times, the Post Office Mission’s purpose was to spread the message of Unitarianism by means of the United States mail. Comins notes, “ It was not a new thing for the stronger churches to send . . . religious literature to the new and struggling churches. . . But the Post Office Mission was to extend a knowledge of Unitarianism to those who applied for it in answer to advertisements in magazines and newspapers.”[25]

As a result of the Post Office Mission new Unitarian groups in the South and West frequently emerged. How to support those in the hinterlands who had heard the message but had no preacher or congregation around whom to develop their new-found faith became the challenge of the women’s organization. In the effort to support struggling new congregations, especially those in the South, the National Alliance and its branches played a substantial role. An 1892 announcement from the Alliance board reminds the women of the special needs of less-established churches: “Every small society should understand that though large and influential churches might be able to dispense with the National Alliance branch, a small society finds in it the very heart of strength and courage, and the more isolated the society the more it is needed.” [26]

Northern Unitarians also often played a paternalistic role for Southern Unitarians, especially when the financial base of a Southern church needed undergirding. Fledgling churches in the South looked North to the denomination’s headquarters for sustenance while they gained a footing and often openly and specifically solicited Northern help. In 1893 the Alliance branch in Atlanta requested any “articles left over from fairs in the North” which they declared would “come to most excellent use” in Atlanta. An 1893 letter from a member of the Chattanooga Alliance branch sounded a plaintive cry for assistance:

I write you in the hope that you may use your influence in our behalf in one of the most difficult periods we have had to endure since our organization. All Souls Church, organized in 1889 . . . has until this year kept steadily increasing in strength, numerically and financially, and has secured very satisfactory recognition in the community. It is one of the outposts of the Unitarian work and has been frequently gladdened by kind remembrances from Northern churches and individuals. Naturally, the stress of great financial or other disturbances falls most heavily on new communities, and ours is poor. Even the comparatively rich are poor now, because their investments are in manufactories which are lying idle or in real estate which is unproductive. There is a mortgage on our church building , due January 1, which we are anxious to pay off. In ordinary times there would be no difficulty; now we are obliged to cry to our Northern friends, “Come over, and help.”[27]

As the Alliance women attempted to coordinate their missionary efforts with those of the male-led American Unitarian Association some subtle conflicts arose, most of them over areas of responsibility. An 1896 explanation about an A.U.A. communique is illustrative:

“The attention of the board was called to the perplexity of many of the secretaries of the Branches over an enclosure of circulars sent to them recently from 25 Beacon St., Boston. The board desires to assure the Branches that the circular touching Post Office Mission work is simply the proposed plan of the treasurer of the American Unitarian Association for a wider effort at church extension. It in no way affects the present or future work of the Post Office Mission of the Alliance, which will be carried on as heretofore.[28]

In general, courtesy and respect prevailed, and much harmony was achieved by the creation of the Committee of Conference, composed of members of both organizations and whose purpose was “to maintain careful communications . . . in order that all field work may be done in the closest sympathy and co-operation, the general plan being to have the Association stand ready to take charge of all movements which the Alliance has created from the small beginnings of Post-office Mission circles, and brought to the maturity of preaching stations or pastors in a preaching circuit.”[29] In 1909, Alliance President Emma Low would note that the Committee on Conference had “been especially helpful in the Southern Missionary work,” and, indeed the committee would prove an excellent support for the joint ventures, as would the attitude of A.U.A. President Samuel A. Eliot.[30]

Eliot’s 1900-1927 term of leadership at the A.U.A. overlapped the years of Southern missionary work and The Carolina Industrial School. His willingness to work with the women of the Alliance was evident to them, and his appreciation of learning and education unquestionably aided the work in the South. “His enthusiastic backing of the schools [at Shelter Neck and Swansboro] seems to have had two personal motivations, over and above the obligation of his office to foster them: his commitment to missions and his envy of the handyman,” notes his son-in-law biographer. Eliot would be present at the 1900 dedication of the chapel at Shelter Neck and would later serve as Board President of the Carolina Industrial School upon its incorporation in 1911. In appealing for financial aid for the North Carolina schools his arguments to prospective contributors were that such investments would net a return “in better citizenship, higher standards of living, happier and more useful lives.”[31]

In the mid-1890s reduced income at the American Unitarian Association obliged its leaders to rein in its missionary efforts in a move referenced in the Alliance minutes as the A.U.A.’s “retrenchment.” In October 1893 Mrs. Chaney, “about to leave for her winter work,” lamented the situation for the South, noting, “The American Unitarian Association has decreased its appropriations twenty-five percent, and this deficiency must be met in some way. . . Without money many interesting openings . . . cannot be followed up.”[32] In the wake of the cutbacks the Alliance was drawn in and became even more involved in the Southern work. It seems clear that the Chaneys’ influence persuaded the women to deepen their commitment to the region and whose plan provided a structure by which the work could be carried on. The 1893 January minutes document Reverend Chaney’s persuasive powers:

Rev. Mr. Chaney, being in the building, was invited to tell the board something about the Southern work. . . .The American Unitarian Association thinks it can only support men who can start churches in centres of population. Considering its present resources, Mr. Chaney agreed with this policy. [Southern rural missionary] work would not at once result in churches. . . . Mr. Chaney appealed to the Alliance, saying, “The truth is, the women have made a great constituency in the South, even if they have not heard of it, through many letters.” He was coming across the result of the work at every turn; and he hoped that, if it approved, the Alliance would encourage [southern missionary work] by helping. . . [33]

A published report from the January 1895 Alliance board meeting explains how the “southern circuits,” which were supported almost solely by the Alliance by the end of the century, came under its protection:

Rev. Mr. Chaney, the Southern superintendent for the American Unitarian Association, was received by the board, and gave a most interesting account of the Southern field. Mr. Chaney enlarged upon the proposition he had before made of sending resident ministers on missionary “circuits” in their own sections. This the ministers will willingly do if traveling expenses can be assured. Mr. Chaney has formulated a plan for such circuits which would cover a large part of the Southern States. The [Alliance] Branch of the First Parish, Dorchester, has already appropriated $200 for one such “circuit”; and it is hoped that other single Branches, or two or more uniting to send one man, may enable Mr. Chaney to fully carry out his wishes. . . .If any Branch desires it, direct communication can be established between it and the person engaged in the proposed circuit work.[34]

A section of the board minutes of those months further clarified where the circuit work would be done and Mrs. Chaney’s role in the effort:

The [Appeals] committee again recommends church extension work in the South by means of traveling circuits, to be distributed among various ministers on payment of their traveling and other necessary expenses, estimated at $200 a year. It is thought that such work will be very valuable in arousing new interest in our faith. If any Branch is willing to appropriate money for such preaching, Mrs. Chaney will receive it, making quarterly remittances to the preacher, and receiving regular reports through Mr. Chaney. Correspondence can also be carried on between those especially interested at the various points and the Branches aiding the work. Such correspondence may result in the formation of Alliance Branches, even if no church is formed… These circuits embrace various points in Virginia . . . in Western North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee under Rev. H. A. Westall, central station Asheville, N. C.; in North And South Carolina under Rev. H. A. Whitman, central station Charleston, S. C.; in Georgia under Rev. W. R. Cole, central station Atlanta, Ga.; in Florida under Rev. J. C. Gibson, central station Edwards, F.; in Louisiana under Rev. W. C. Pierce, central station New Orleans, La.; in Tennessee under Rev. S. R. Free, central station Chattanooga, Tenn.; in Texas under Rev. Emily Wheelock, central station Austin, Tex.; . . The circuit of East Tennessee, in care of Rev. H. A. Westall, has already been taken by one of the Alliance Branches. It will include, as visiting points, Knoxville, Tenn., Greenville, SC, Western NC, etc.[35]

In the spring of 1896, because of reduced funds available for the support of work in the South, Reverend Chaney resigned as Southern Superintendent. At the Alliance board meeting in September Mrs. Chaney submitted her resignation as Vice-President for the Southern States. Both departures were mourned by the Alliance women, the March minutes noting, “among Unitarians throughout the South is heard the expression of great sorrow at the resignation of the Southern Superintendent. . . ..”[36]

Mrs. Chaney’s successor, Mrs. Anna Moss of St. Louis, made an emotional speech at the opening of the 1897 Southern Conference, noting “Mrs. Chaney’s absence . . . is not only a great loss to our Cause, but a personal sorrow to each. . . On the other hand, our recognition of her service would be unworthy, did we not gather new courage.” Mrs. Moss was also able to announce the Alliance’s proposal for supporting the Southern Unitarian effort after the Chaneys’ departure, an overture which, Mrs. Moss said, “needs but to be understood by us. . . in that cordiality never refused by a Southerner to a sincere proffer of friendship.”[37] The plan, which had been worked out under the leadership of Mrs. Abby A. Peterson, an Alliance Director, assigned a “strong branch in the north” to each of the young Alliance Branches in the southern areas. The Alliance Minutes record the plan and Mrs. Peterson’s leadership in its operation:

Mrs. Peterson reported that, concurring with Mrs. Chaney in her request that the southern branches so soon to be left without a superintendent should each be put into communication with a strong branch at the north, she had suggested the matter to the Suffolk [County, Massachusetts] branches and made arrangements as follows: That Church of the Unity, Boston should take Richmond; Roxbury, Asheville; New South, Highlands; Bullfinch Place, Charleston; First Parish, Greenville; [unreadable name], Atlanta; Church of Disciples, Memphis; Chelsea, New Orleans; Jamaica Plain, Austin; Brighton, San Antonio. Circuit work in Florida through Mr. Gibson was undertaken by the Arlington St. Branch.[38]

Noting that “there are now fourteen churches in the Southern Conference and fifteen Alliance Branches,” the National Alliance of Unitarian Women at the end of the century was thoroughly involved in the South, taking up, as the Chaneys had hoped, where the American Unitarian Association had bowed out. Mrs. Abby A. Peterson, who had been elected to the Alliance Board in 1895 as a Director from the strongest district in the Alliance, would, with the branches in her Suffolk County constituency, become directly involved with the southern work in the wake of the Chaneys’ departure. Mrs. Peterson’s experience would propel her into the chairmanship of the soon to-be-created Southern Work Committee, in which capacity she would, in the early 1900s, recommend that a chapel be built at Shelter Neck, North Carolina. Her–and the Alliance’s–involvement with the Shelter Neck community would be extensive and would continue for more than twenty years.

Chapter II

THE CHRONICLE OF SHELTER NECK’S UNITARIAN SCHOOL

1900-1910: THE BEGINNINGS OF THE “DIX HOUSE SCHOOL”

How did the school happen to be there? I only know it began with a church, or perhaps I should say, with a preacher. This man became a Unitarian and asked the Unitarians in Boston to help him. It seemed to him, as it did to our New England ancestors, that the school was an important adjunct of the church. Edith C. Norton, 1924

Shelter Neck, North Carolina, was not a spot the American Unitarian Association would likely have targeted for a liberal religious congregation in 1900. Yet the remote community became a center of Unitarian activity for over a quarter of a century, an accidental and ironic anomaly in the denomination’s history. Known to posterity as The Carolina Industrial School, the Unitarian settlement school at Shelter Neck had its beginnings in the involvement of the National Alliance of Unitarian Women in denominational extension in the South. Yet the “Dix House School,”as the community of Shelter Neck knew it, would surely never have existed had not the Reverend Joseph G. Dukes become Unitarian and gained the National Alliance’s support to preach in eastern North Carolina. The Alliance backed Dukes’ wish to build a chapel, a parsonage, and a schoolroom, resulting in the organization’s becoming a property owner in Pender County. By 1905 the Alliance decided to use the property for an “experiment in settlement work,” and from that beginning the larger school enterprise grew. What began at the turn of the century as an effort to sustain the tenuous Unitarian presence in the South ultimately planted the Carolina Industrial School, which operated at Shelter Neck until 1926.

The Reverend Joseph G. Dukes’ North Carolina circuit had been supported since the mid-1890s by the A.U.A. and the National Alliance. Most probably Dukes was a convert to Unitarianism; Comins asserts, undoubtedly based on a 1930 report in the Alliance records, that he had previously been a Baptist and became Unitarianism through reading the pamphlets of the Post Office Mission. Although little other information is recorded about him, Dukes likely was a Southerner who had previously preached for another faith. His name was first mentioned in Alliance records in an 1895 discussion about Southern missionaries:

Mr. Gibson of Florida and Mr. Dukes of North Carolina are working in fields untilled by other liberal Christians. They are earnest men, working in the true spirit among people grateful and responsive to their work, and yet able to do little for their support. Unless we help them, no one will. . .

In the ensuing end-of-the-century years, Alliance board minutes frequently mentioned Dukes and Gibson and the “southern circuit work.” The regular “appeals” to member branches through those years included financial support for the two, and, underlining the importance the organization attached to their work, an 1898 address by President Mrs. B. Ward Dix cited the work of Dukes and Gibson as two of the “three missionary enterprises likely to need assistance for several years.” Later in 1898 the Alliance financed Dukes’ and Gibson’s expenses to attend the upcoming Southern Conference, noting that “the two missionaries of the Alliance. . . are in a wilderness, isolated and unable to meet other ministers . . . [I]f they could tell of their work to the whole Conference it would help the Conference and give others an opportunity to help them.”

In March 1898, seemingly in a quandary about how supportive to be of the missionaries, especially of Dukes, the Alliance sought retiring Southern Secretary George Chaney’s opinion: “Rev. Mr. Chaney was “invited [a revision in the handwritten minutes shows this word substituted for “admitted”] into the meeting. . . Of Mr. Dukes he did not know . . . but told us of the conditions under which he had seen the work of Mr. Dukes. He advised care and broad supervision and thought the officers of the branch at Charleston might help.” In April a letter from Reverend Mr. Whitman, of Charleston, was read “speaking earnestly concerning the good work of Rev. Mr. Dukes.” The Alliance board voted to continue its assistance to Dukes and provided “that the branch at All Souls’ Church, Roxbury, [Mass.] would assume the friendly care of his work.” By 1899 the two missionaries were even more prominently mentioned in Alliance records, the reports and letters often read by Mrs. Abby A. Peterson, who became more and more involved in the “southern work” as the Chaneys withdrew from the region.

The Alliance minutes reflect the distance these New England women felt from the Southern enterprises, however. The Southern climate and culture were, clearly, unfamiliar to them. An 1899 section reports that “Mr. Dukes preaches every Sunday to one or the other of the <churches’ [quotations are those of the recording secretary] started by him.” When Alliance President Mrs. B. Ward Dix and A.U.A. President Samuel A. Eliot attended the 1898 Southern Conference, Rev. Eliot observed that “many of the enterprises in the South [are] not yet beyond the stages of experiment. . .”

The spring 1899 minutes note the annual compensation for the two missionaries: Gibson was being paid $500 and Dukes $300. At the national meeting that year a talk by Dukes was one of the centerpieces of the convention. A report circulated to the Alliance branches noted:

Mr. Dukes made a strong impression, not only upon his audience, but also on the people with whom he came in contact in Washington. His simple but enthusiastic statement of the work he is trying to do, the long journeys he takes, the people he reaches, and the great hope he feels in the success of his efforts, made his story a most telling one, and those who heard it will not soon forget.

At the end of 1899, Dukes proposed building a chapel in his circuit–but the site he originally mentions is Prospect, not Shelter Neck. The Alliance women seem unsure of Dukes; they are reticent to be directly involved in the building of the chapel and decide that “before further steps were taken Mrs. Chaney [retired from her previous Alliance position but still accessible] should give the board such information concerning Mr. Dukes and his work as she may be able to gather.” In December “the President and Mrs. Peterson were chosen a committee to consider the erection of Mr. Dukes’ chapel at Prospect.”

In early 1900 Dukes’ letters suggested that Shelter Neck might be a more promising spot than Prospect. In the spring months of 1900, having secured five-year pledges from Alliance branches to support “the southern circuit work,” the Southern Committee recommended that “all additional money shall this year be spent to strengthen the work of each [missionary] by assisting to buy or build a church.”

In June 1900 the Alliance moved more assertively: “It was voted that the board approved . . . sending someone to view the situation and report.” By July Mrs. Abby A. Peterson, appointed by Mrs. Dix, had visited Mr. Dukes’ circuit in North Carolina. Her report in the July, 1900, minutes introduced Shelter Neck to the Alliance and secured the board’s support:

Mrs. Peterson gave a full account of her visit to Mr. Dukes and the conclusion to which she arrived. Six miles from Burgaw at Shelter Neck seemed to be a suitable place for a chapel which is much desired by the people. Mrs. Peterson had promises of land, lumber, nails and work which would leave only a comparatively small amount to be raised. . . [I]t was voted that $250 be appropriated for building a chapel at Shelter Neck, North Carolina. . . [I]t was voted that this amount be placed in the hands of Mrs. Peterson to be advanced as she thinks best. [I]t was voted that Mrs. Peterson be authorized to expend such additional sum as might be reasonable to complete furnishings, pay freight, etc. . .

The desirability of securing a home for Mr. Dukes in the vicinity of the new chapel was considered and . . . it was voted that Mrs. Dix have authority to expend one hundred dollars of the sum especially given to her for the use of Mr. Dukes and his work, if in the judgement of Mrs. Dix and Mrs. Peterson it becomes wise and expedient to do so.

The Shelter Neck chapel was completed in time for a dedication on November 16, 1900, when, because A.U.A. President Samuel Eliot and Alliance President Mrs. B. Ward Dix were already in the South, they would both be present for the day-long services. Having the new structure ready by that date was clearly intentional; the October minutes note that “the chapel is progressing rapidly, and it is expected that it will be finished early in November. An effort will be made to have it dedicated about the same time as the meeting of the Southern Conference, and to have the President of the American Unitarian Association and the President of the Alliance take part in the services.”

The years 1900-01 marked a decided upswing in Unitarian activity in North Carolina. Not only were the chapel and a parsonage built at Shelter Neck, but Dukes was also preaching in Swansboro and other nearby points. The Alliance minutes in late 1900 provide a glimpse of the increased activities:

[Dukes] held three services at Wells Chapel, a Baptist church, where he had large congregations and distributed papers and tracts. At Island Creek his congregation was divided, as there was preaching in different places on the Sunday when he was there, but the people are much interested. . . Will the branch that has been sending literature [to him] please accept his thanks. Both he and his wife are reading the sermons, and would like to receive more. . . .

Sufficient interest has been aroused in Swansboro to secure a hall which has been hired for Mr. Dukes’ use one Sunday in each month. At Richlands, the Presbyterian church, now without a pastor, has been obtained, and at Green Branch a school-house. This circuit, which also includes Stella is said to be in the most intelligent and progressive section of the county, and much is anticipated from Mr. Dukes’ ministrations.

Swansboro, in nearby Onslow County, would soon attract the attention of the Alliance’s educational workers and the venture there would, together with the one at Shelter Neck, be incorporated as the Carolina Industrial School. While missionary outreach came first and touched almost a dozen communities in the area, only at Shelter Neck and Swansboro would school operations be established. Dukes would soon be joined by the Reverend W. E. Cowan, who would augment the effort to spread the denominational message and who would remain in the North Carolina circuit until his death in 1922. While many nearby eastern North Carolina communities experienced the preaching of these Unitarian missionary ministers over the next twenty or thirty years, Shelter Neck and Swansboro would be the two bases for circuit ministers.

The parsonage for Dukes, for which the Alliance had made a commitment during the winter of 1900-01, was under construction during the spring of 1901. The March minutes reported that “Mr. Dukes’ house will be finished by May first and will cost $1150.” Sometime in 1901-02, though the decision is not clearly documented, the Alliance decided to name the Shelter Neck parsonage in honor of its pioneer president, Mrs. B. Ward Dix. The name for the house was referenced in November 1902 when Mrs. Dix, who had been ill, wrote to the Alliance board suggesting the house be called the Shelter Neck “parish house.” The board overruled her modest request, however, and “ Dix House” was the name that stuck.

By June 1901 Dukes initiated another building venture at Shelter Neck–and this one would have a long-lasting influence: “Mr. Dukes proposes to raise $10 to clear ground for the house or schoolhouse.” The move to add a schoolroom seems to have been put forward by Dukes, not the Alliance, an ironic corner of this story. A 1924 article by Edith Norton, then school superintendent at Shelter Neck, says that “it seemed to [Dukes] that the school was an important adjunct of the church. . . He built a little wing on his house for a schoolroom, and sent North for teachers.” The completed schoolroom was in place by spring 1902 when Miss Ellen Crehore, the first northern woman to come to Shelter Neck for the express purpose of teaching school, visited. This room was the first space to which Shelter Neck children came to school, and, hence, the entire generation of citizens and school alumni refer to the school as the “Dix House School.”

The move to add educational work at Shelter Neck precipitated a lively debate at the board meeting that announced Dukes’ proposal:

Mrs. [Kate Gannett] Wells . . asked to be recorded as disapproving any connection of the Alliance with schools or educational matters. . . Discussion followed on denominational work in general and the southern circuit work. . . Mrs. Wells moved that none of the money received for southern circuit work, shall be used as payment for public school work. The president declared that the money was intended for circuit [ sic] work and would be so used. Mrs. Wells asked to withdraw her motion Voted: “All money sent for the south shall be used for church [sic] work.” The president ruled such a motion out of order as the money was given to southern circuit work. Miss Waldo asked why the question need be brought up at this time. Miss Wells gave reasons why the future work should be guarded and moved that “Southern circuit work does not include specific public school instruction. Voted by those present.

In spite of the objections raised at the Alliance, the “ell” on Dukes’ house was built. Miss Crehore, Shelter Neck’s first teacher, visited in the spring of 1902. She was later present in Boston at the close of the Alliance’s May board meeting and gave “an interesting account of the three months she has just spent at Shelter Neck.” Who or what motivated her visit is, again, unclear, although Edith Norton’s 1924 article suggests that Dukes had a hand in it.

While “Miss Ellen” did not immediately return South, by the fall of 1902 the educational work clearly influenced a request asking “if the [Alliance] Board would be willing to allow the use of the school room at Shelter Neck to the state of North Carolina for a public school for two months if satisfactory arrangements could be made.” The board, in November 1902, “voted to allow the rooms to be so used if desired, and the matter of rent be left to the Southern and Finance Committees.”

The Alliance made no further efforts in educational or social areas in 1903. But in the winter of 1904-05 significant change occurred: the Reverend Dukes resigned, effective November 1, 1904, and, to oversee the transition in leadership and to further acquaint herself with the circumstances at Shelter Neck, Mrs. Petersonwent South. As a replacement for Dukes the Alliance retained the Reverend W. S. Key, an Englishman.

Mrs. Peterson’s report to the January 1905 board meeting called the board’s attention to the challenges arising at the growing enterprise. As a result of her presentation the Alliance formed a special committee to focus on Shelter Neck. While the minutes do not include details of the committee’s work, the results of its efforts are evident in the prominence the North Carolina work is given in Alliance reports that year. One example is the address at the 1905 Annual Meeting by Reverend W. S. Key, “who gave an exhaustive and most interesting account of the circuits in North Carolina.”

The Shelter Neck school, born of the Reverend Dukes’ schoolroom, was begun in the years when settlement houses and schools sprang up in many areas of the country. Toynbee Hall, established in London’s East End in 1884 by a group of young Oxford men, motivated by the notion of personal service to the poor, provided the first internationally known model for settlement work. The concept made a relatively rapid passage across the Atlantic. Hull House, founded in Chicago by Jane Addams in 1889, was one of the earliest and is surely the most famous of the settlements in America.

In America “liberal Christians,” Unitarians among them, were the most ardent supporters of settlement work. The Boston area knew a number of these institutions. Articles about Boston settlement houses, particularly South End Industrial School and Hale House (founded in honor of Edward Everett Hale, a revered Unitarian leader), ran in The Christian Register. A December 1911 Register article claimed that the South End Industrial School was “the only one in or near Boston supported entirely by Unitarian chruches and individuals, and as such it should have a wider recognition.”

While most settlement work was directed toward city neighborhoods, the idea made its way to rural areas and to the South. The most famous settlement work in the South was done in the mountains of Appalachia, but some settlements were established in other areas, a1937 article, “The Settlement Movement in the South,” noting that the first such institution in the South was founded “for Negroes in 1893 by Mabel W. Dillingham and Charlotte R. Thorn at Calhoun, Alabama.” Unitarians supported the Calhoun school as well as the Southern Industrial School (for white children) at Camp Hill, Alabama, whose founder, Lyman Ward, would later serve on the Carolina Industrial School board and whose graduates would from time to time teach at the North Carolina schools.

The women of the Alliance were surely familiar with settlements both in concept and practice. Women were the backbone of settlement work in America–and especially in the South–and it is unthinkable that these liberal Christian women of Boston would not have been conversant with these ideas. Indeed, a bibliograpy of writings about settlement work notes that Caroline S. Atherton, a long-time member of the Alliance’s executive board and a frequent member of the southern committee, was the author of an essay on the subject. Both Mrs. Atherton and her attorney husband, Percy A. Atherton, would be involved in the Carolina Industrial School.

The term “Shelter Neck Settlement” first appears in board reports in 1905. In the October minutes, “Mrs. Atherton spoke of the furnishings needed in the [Dix] house and the expectation that an experiment in settlement work would surely be begun.” The committee for “the Shelter Neck Settlement” asked for a loan for the settlement work from the “southern fund” and also reported that the property–the Dix House with Mr. Dukes’s attached schoolroom–was now secured, with “Mrs. Everett and Miss Hawes to undertake the settlement and school experiment.”

The year 1905, clearly, marked a turning point in the scope of work at Shelter Neck. Most later stories about the “Dix House School” cite this year for its founding, although some, being aware that 1902 was the year when the “ell” was built for teaching purposes and when Ellen Crehore first visited, claim that year as the school’s beginning. The progress of events which the Alliance board minutes reveal, although the settlement and educational work’s start-up decisions are not detailed, is clear evidence that a commitment for work beyond denominational expansion was made in the winter of 1905-06.

When school opened in October 1905 the chapel and the “Dix House” were in use by students, teachers, and the circuit minister. Classes met in the schoolroom of the Dix House, the teachers and ministers lived in the adjoining main house, and the chapel was used for religious services. Mrs. Peterson, now becoming a permanent resident in North Carolina, was working for the first time with Mr. Key and without Dukes. Miss Hawes and Mrs. Everett were the first full-term volunteer teachers. Mr. Key was the circuit minister in residence, although he is not remembered to have done any teaching. The January 1906 minutes “report the success of the school in the Dix house–25 pupils from 5 to 33 years of age” and acknowledge the Alliance’s receipt of a deed to “the property at Shelter Neck to be known as Dix House, and to be used as headquarters for our missionary work in that section and as a parsonage for our representation, as long as it remains in the possession of the National Alliance.”

A brief history of the Shelter Neck school, almost surely written by Reverend W. S. Key (although no author is credited in the document), explains the Dix House “ell:” “The object in view, when the buildings were erected, was the providing of a rural school for the benefit of the children whose homes were in the immediate neighborhood, the nearest schoolhouse being over two miles distant. Several of the families had no less than a dozen children in each household.” The same document–which will be referenced here as “Key’s history”–describes the first years at the school:

. . . These two estimable women [“Mrs. Everett and her friend Miss Hawes”], accepting the urgent invitation of Mrs. Peterson, went to Shelter Neck [in the fall of 1905] and soon had the school work under way. At first there was some hesitation shown by the parents of some of the children about attending the school which was owned and was to be carried on by Northerners [sic]. Very shortly, however, as it became known what excellent teachers there were at Dix House school, and that they did no proselytizing for Unitarianism, (as it had been predicted they would) the attendance began to improve, so that the limited accommodations were taxed to the utmost. For six months the school work went along smoothly and satisfactorily, and when the term drew to a close, in the spring of 1906, there was a crowded attendance of parents and neighbors at the closing exercises, which proved a revelation to all the community who didn’t hesitate to express their astonishment and delight when they discovered how apt at picking up the rudiments of education (the “Three R’s”) their children were when under the care of and receiving the instruction from competent teachers. Many were the compliments paid the teachers for the work they had done. . . Indeed, so marked was the kindly and neighborly feeling which had been evoked between the entire community and the Northern teachers that the latter resumed their labors in the fall of 1906, and during the next six months conducted a still more successful school, with a larger attendance, increased enthusiasm and ambition, and with a still fuller measure of all round success.

. . . At the closing exercises at the end of [the 1907-08] term there was again a large attendance of parents, friends and neighbors, and so satisfactory were the results of the instruction that the same teachers [Clapp and Warren this term] accepted an invitation to return in the fall, which they did with most gratifying results, for by this time the school had gained an enviable reputation among the educational institutions of the State.

Key’s history continues, in similar vein and style, to explain that the school term at Shelter Neck “never exceeded six month’s duration, always beginning on or about the first day of October and continuing until about the first day of April, these being the slack months among the farmers and planters, when the children are free from out of door labors.” He adds, furthermore, that such a schedule was workable, too, because the days beyond April brought “increasing temperature which is far from agreeable to persons brought up in the north and who feel the effect of the southern heat greatly.” At the close of the 1910 term “the outdoor exercises. . .aroused so great an amount of public interest and were attended by so large a crowd from all the countryside that they have been continued ever since and have become an established institution.” By the fall of 1910, Key says, “the school had become known all through Eastern North Carolina.”

At the Unitarians’ annual gathering in Boston in May 1906, Dr. Edward Everett Hale, by then one of the denomination’s confirmed elder statesmen, declared in his opening remarks, “The Alliance is the best thing we have. It is up with the times. The women can do what they want to do now; to say what they want to say now; and they can do it together. The Alliance is wide awake, it is the best conducted business I have seen.” In North Carolina, at least, the Alliance had begun one of his most significant projects.

1911-1919: THE HEYDAY OF THE CAROLINA INDUSTRIAL SCHOOL

We had a French teacher who taught us French and we had sumptuous dinners and we danced the Virginia reel every Saturday night. It was a lovely place and we just had a lovely time and I’m just happy I could be a part of it. Clara Deal Watkins – 1993

The 1911 incorporation of the North Carolina school operations as “The Carolina Industrial School” facilitated the expansion of the work at Shelter Neck work and brought it to the peak of success. The greater measure of attention the school enjoyed after 1911 increased its financial support and allowed it to pay salaries to its staff and to enlarge its physical plant. The new corporation’s board of trustees, headed by A.U.A. President Samuel A. Eliot, was filled by some of the more prominent leaders of the Unitarian movement. Mrs. Abby A. Peterson remained the school’s superintendent and indefatigable promoter, and she, along with the Reverend W. S. Key, was based at “the Dix House, Shelter Neck” for most of each year, returning to New England in the summer months to recruit staff and raise funds. In a June 1911 article in The Christian Register , A.U.A. President Eliot introduced the newly incorporated school:

[N]ew enterprises allied to our general denominational work have come into being during the last winter. The incorporation of the Carolina Industrial School has provided for the enlargement and continuance of the educational work which has grown up in connection with the group of Unitarian churches which was originated by the Women’s Alliance in Pender and Onslow Counties, North Carolina. The new corporation has taken over the school properties. . . and expects soon to increase the equipment of the schools and enlist the co-operation of new friends. Mrs. Peterson, who has been from the beginning the moving spirit in this work, has been presenting this cause to a number of conferences, churches, and Alliance branches in New England, and we may confidently expect that the Carolina Industrial School will soon take its place among the formative and uplifting influences for the white boys and girls of Eastern North Carolina.

Many issues of the Register in 1911 carried articles about the North Carolina school. Most applauded the “pioneer work” of Mrs. Peterson, Mr. Key, and the volunteer teachers and stressed the need for contributions. In a particularly long piece Henry Wilder Foote, the A.U.A.’s Secretary for Education and a Carolina Industrial School board member, described for the Register’s largely northern Unitarian readership the school’s setting and facilities and revealed his own opinion about its possibilities:

Shelter Neck is a rural community. . .the number of pupils ranging from 25 to 45, of all ages and sizes, that being as many as can be crowded into the school-room. Dix House, and four acres of land adjoining the church property, belong to the National Alliance, the house having been intended as a parsonage. . . Being housed thus, the school has heretofore cost but very little. It is to be hoped, however, that means can be found to develop its work. The greatest blessing which we could confer upon this district, and I believe, the strongest method of reinforcing our churches as well, would be to develop this little school into a modest industrial and agricultural school. With proper accommodations boarding pupils could be taken, and they would come in from all the localities where we have churches. They would get training of a kind which is now practically unobtainable, and for want of which many of them are growing up almost illiterate.

Foote’s stated goals for the school were successfully realized over the next ten years: the Carolina Industrial School expanded its facilities and curricula and became widely respected in the state. In 1912 a new separate school building provided two large classrooms, an auditorium, and a library which doubled as a principal’s office. Key’s history points out that “the classrooms were equipped with individual desks and stools; the library with shelves which now accommodate a valuable library of books, numbering nearly 2000 volumes, while the auditorium is available alike for class work, social meetings and special school and community gatherings.” The new schoolhouse was dedicated on October 30, 1912, with “the building crowded with pupils, parents, and friends” and speeches made by the Rev. A. T. Bowser of the Unitarian church at Richmond, Virginia, Mr. Archibald. M. Howe of Cambridge, Massachusetts, “and other friends.” Also in 1912 additional acreage and a second house, financed with a contribution from Miss Ellen Kimball and named Kimball House, were acquired. These added properties afforded the school considerable farm land and allowed, in the fall of 1912, four girls to be the first female boarders while two boys were the first to stay in Dix House.

Key’s history offers the most detail on record about the curricula at the Shelter Neck school. The “usual courses of academic studies” were taught alongside other multifaceted curricula, he writes. “The primary grades were instructed according to established kindergarten methods, including clay modeling in which some of them excelled.” With the arrival of some teachers with special talents, “musical, literary and dramatic entertainments were given occasionally.” Key singles out Miss von Lavner , a teacher proficient in music and languages, noting that “with the addition of this lady the study of French became part of the course of study. . . [and] occasionally recitations in French were delivered in public.”

“The older girls,” he continues, “were taught sewing, basketry and rug weaving, one of the rooms in Kimball House being equipped with an old time hand loom on which the girls quickly learned how to weave most attractive rugs.” In addition to the teachers, housekeepers were frequently retained at Dix House, and, one of them, Miss MacIntire, “held regular classes in cooking at Dix House for the boarding pupils, who were taught bread making and the preparation of all kinds of good wholesome food, and the preservation of vegetables and fruit. Miss MacIntire likewise gave regular lessons in millinery to all the girl students. . . [and she] remained at Dix House throughout the whole of the summers of 1917 and 1919 during which season she assisted in preserving literally thousands of cans, jars and bottles of fruit and vegetables for the Dix House family’s winter use.”

If the girls were being taught domestic skills, the boys were being offered the training which Foote must have, specifically, had in mind: agricultural and industrial instruction became such a successful program that the school became known for it around the state. There was, Mr. Key writes, “a commodious and well equipped workshop which was built soon after the new schoolhouse was completed.” Boy students were taught “the use of mechanical tools. . .to repair boots and shoes, carpentry, making and repairing harnesses, farm tools and agricultural implements, buggy and wagon work, etc. . . . “

As the school’s agricultural and industrial programs for boys and girls expanded, the school’s leadership reached out to connect its production with the surrounding area. To Key, Mrs. Peterson “was the leading spirit in the organizing of county and community fairs, neighborhood welfare societies, school exhibitions and other uplifting movements.” She was able to “display every conceivable kind of school work in most attractive exhibits which invariably gained the notice and attention of all visitors. . . and the Carolina Industrial School always won the highest honors, the judges being invariably State experts in their respective departments.” Key obviously relished these successes and added a tale of an event in nearby Wilmington, North Carolina: at the Annual Corn Show, which he gives Mrs. Peterson credit for helping organize, “a New York financial and railroad magnate, whose summer home was located near that city, was so attracted by the beauty of these hand woven rugs that he bought every one then on exhibition and gave orders for additional ones.”

Whatever other fairs Mrs. Peterson organized, the events for which the school became most well-known were the “Farmers Institutes.” Key’s history says they were organized by the Department of Agriculture and held once or twice during the school term. Five or six “expert agriculturists, botanists, horticulturists and veterinarians equipped with lantern slides, diagrams, and specimens of almost every conceivable variety of Southern fruits, grains and vegetables” would give presentations and addresses, “the meetings being attended by a large crowd coming from all parts of the County,” he writes. The fame of these “Institutes” spread even to the pages of the Unitarian Christian Register, where a 1914 article, “From Shelter Neck,” paints a colorful picture of them: